>

> Bruce Karney

>

> The Future of Solar Energy Incentives in California

>

>

> California’s movement toward a renewable energy future has been

> accelerated by government subsidies for solar-produced

electricity,

> notably the California Solar Initiative’s (CSI) Million Solar

Roofs

> Program. The Million Solar Roofs Program launched in 2007

with the goal

> of stimulating the installation of 3,000 megawatts of new solar

power

> systems by 2016.

>

> Subsidies were initially set at $2,500 per AC kilowatt or 39 cents

per

> kWh produced in the first 5 years. That covered about 20% of

the cost

> of a system, and federal tax credits paid for another 30%. The

incentive

> program was designed so that the incentives would reduce in steps

over

> the 10 years of the CSI. These reductions have taken place

somewhat

> faster than expected. The incentive is now $250 per AC

kilowatt in PG&E

> territory.

>

> As the CSI program approaches its end and other programs such as

net

> metering are facing scrutiny from utilities, there is concern from

> environmental organizations and solar equipment makers that

California’s

> movement toward a cleaner energy future may stall.

Experience in other

> countries has shown that poorly designed and administered

incentives and

> requirements can produce a boom and bust cycle in the solar

business.

>

> Bruce Karney has been involved in solar photovoltaics since he

organized

> a group purchase of solar panels in 2007 in which 119 Mountain

View

> homeowners bought solar PV from a single vendor at a deep

discount.

> Since then he has worked in marketing and customer finance at

SolarCity,

> California's leading residential solar design, installation and

> financing company. He is currently Marketing Operations

Manager at

> Skyline Solar, a Mountain View based manufacturer of

> medium-concentration photovoltaic systems. Bruce will review

the state

> of solar subsidies in California and elsewhere and offer his

thoughts on

> what the future may hold.

>

Bruce began by breaking the role of

government in solar pricing over time into three eras. The first was

the era of carrots, the second the era of sticks, and the third will be

the era of market forces. The era of carrots was started back in the

1970s, when government instituted subsidies to jump start the industry.

This era is expected to end in 2013. The second era is the era of

sticks, when regulations require a certain percentage of renewables in

utility portfolios. The third era is going to be the era of market

forces, when supply and demand will meet in the marketplace at a price

set by negotiation.

Carrots usually take the form of tax credits or rebates. For example,

when Bruce got together a solar buying club in 2007 there was a

$2,500/kilowatt incentive from the State of California (part of the

Million Solar Roofs program). In addition, the U.S. Govt. offered tax

credits for such systems that lowered the cost by $2000. The CSI

program will end in 2013 in PG&E territory, and it is unlikely to

be renewed. The explosive growth of solar panel supply, coupled with a

slowing of the growth of demand, caused solar panel prices to fall by

50% last year and price reductions are expected to continue in 2012-13,

though at a much slower pace.

Sticks are expected to take the form of

portfolio resupply and demand are not adjusted by government

regulations. In such

an environment, for renewable energy For example, PG&E is expected

quirements. For example, PG&E is expected to provide

25% renewables by 2016 and 33% renewables by 2020. Because utilities

have found that people get much more angry when the power goes out than

they do when the price goes up, it is expected that price signals

(higher utility bills) will be a key part of adjusting power demand so

that the available renewable supply will be the mandated percentage of

total power generation.

Market forces determine price when the

supply and demand are not adjusted by government regulations. In such

an environment, for renewable energy For example, PG&E is expected

to provide 25% renewables by 2016 and 33% renewables by 2020.to succeed

it must be cheaper on a per kW/Hr basis than the same amount of coal

based power. Currently that price is about six cents per kilowatt-hour.

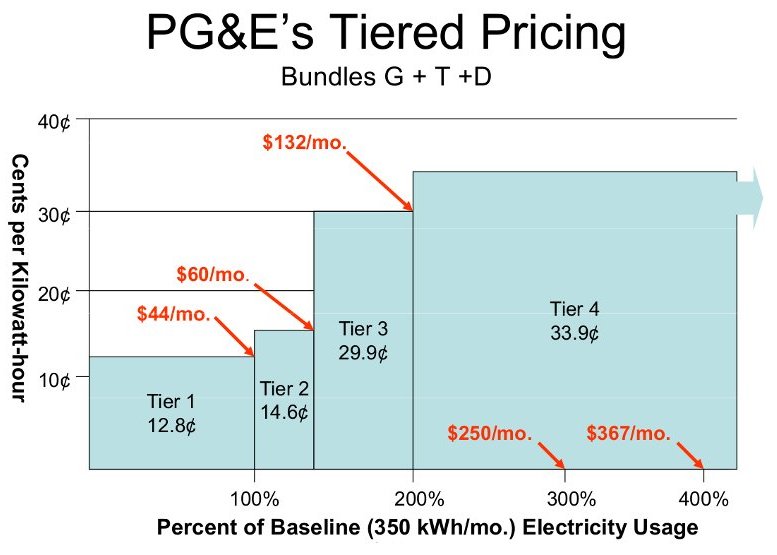

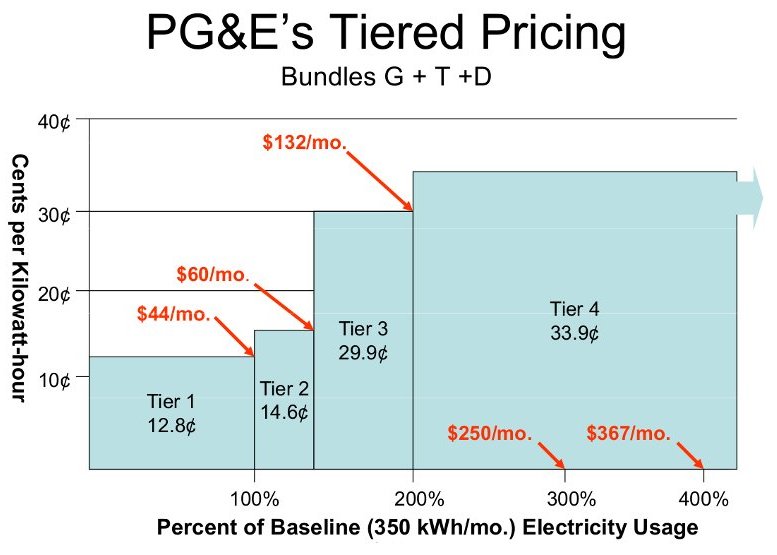

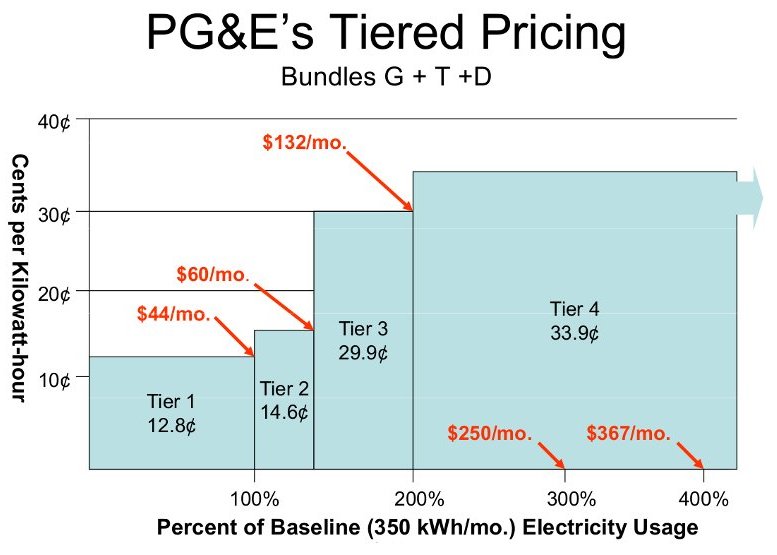

Bruce explained how market forces work with the following graph of

California's power pricing by our largest utility.

Customers who spend more than

$132/Month on power are paying 33.9 cents per kWh for some of their

power. It is a no brainer to install solar systems that supply that

percentage of the load. Many, many people and companies have done so.

If Texas had a pricing policy like this one, they would have much more

installed solar than they do. Texas is hot compared to California.

Since every kWh used there costs the same coming out of the plug there

people have no incentive to conserve the way we do here.

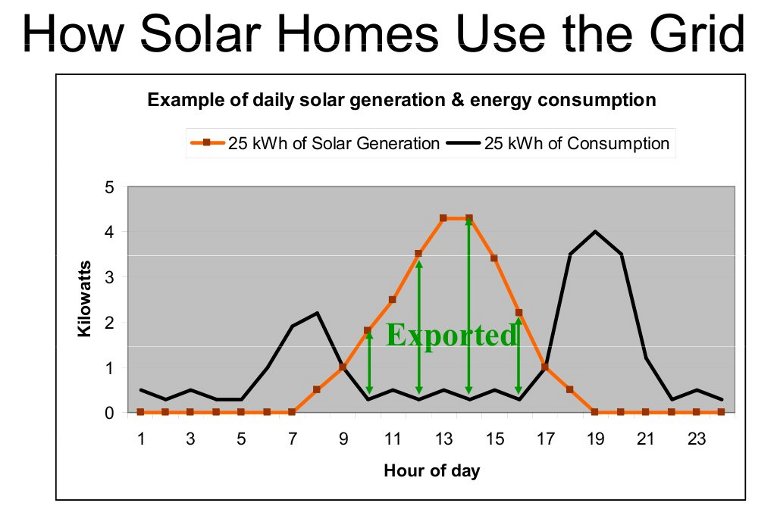

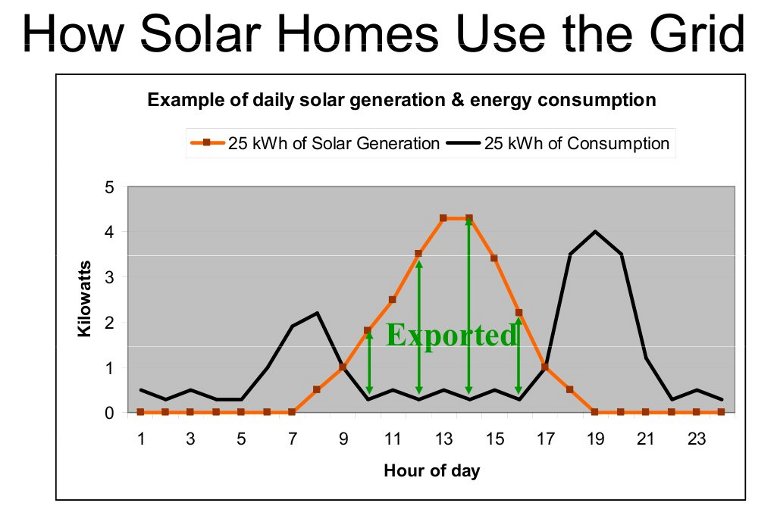

Solar systems come in a variety of

configurations. The most cost effective is a grid tied system, using

the power grid as a battery. The way that works is that the system

pumps energy into the grid during the day, when the sun is shining.

(That's the green area on the chart.) This works out well for the

utility, since most of their peak demand comes during the day. Then at

night the system absorbs power from the grid. A properly sized system

will balance out supply and demand, so that at the end of the year the

net cost to the owner is low.

For years and years the government has

set the percentage of the power portfolio that can be supplied by

solar. At first it was 1%, then later 2%. Now it is up to 5%, but the

utilities are haggling with the incumbents over what that means. Five

percent of total possible supply? Five percent of a normal days supply?

The differences between these numbers are large enough that the

lobbyists are investing a lot in the discussion.

During Q&A a number of interesting points came up:

If your power bill is in the $100-$150

per month range, a solar system would cost you about $8000 to install,

and will pay for itself in about five to eight years.

No new Municipal Utility Districts have

been started in California recently, although Marin County and San

Francisco are at least talking about it.

If you want to get rid of First Solar

panels, just call up the company and they will come get them. This is

partly because they contain Cadmium and Tellurium, toxic metals. Most

solar panels contain a bit of silver. Maybe you could get a few cents

from scraping it off. In most systems the power inverter fails before

the panels, which amounts to a roll-on suitcase sized ewaste pill when

it's replaced. The solar panels themselves can last many years.

Solar policy positions aren't enough by

themselves to decide which Presidential candidate to vote for, but

clearly Obama's solar policies are better than Romney's.